Economic crisis in Sri Lanka

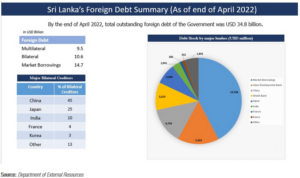

Beginning from mid-2019, Sri Lanka has been facing its worst economic crisis since gaining independence in 1948 and at its peak, Food inflation reached a maximum of 94.9% in September 2022 and Non-food inflation reached 64.7% in October 2022. Resulting fuel shortages and lack of access to other imported goods as well as skyrocketed cost of basic necessities, created public unrest nationwide. Amidst the unprecedented levels of inflation Sri Lankan government declared in April 2022 that they are unable to make the due payments on foreign debt, becoming the first country in Asia-Pacific region to go into sovereign default in this century. As per Department of External Resources, by the end of April 2022, total outstanding external debt of the central Government was USD 34.8 billion.

In March 2023, International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved a USD 3 billion loan under a new Extended Fund Facility (EFF) arrangement of 48 months to support Sri Lanka’s economic policies and reforms which include major tax increases and higher energy costs which so far has been unpopular among the general public. As IMF loans are a shirt-term solution, this approval will be proceeded by negotiations between Sri Lanka’s bilateral, multilateral, and private creditors on debt restructuring which gives the opportunity to consider Debt-for-Climate swaps (DFCS) as an alternative.

How does DFCS work?

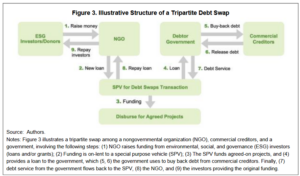

Debt-for-Climate swaps (DFCS) are inspired by “debt-for-nature” or “debt-for-development” swaps and as defined by IMF working paper on “Debt-for-Climate Swaps: Analysis, Design, and Implementation”, they are “partial debt relief operations conditional debtor commitments to undertake climate-related investments”. This could be either bilateral debt swap where the previously committed debt to official bilateral creditors is redirected to the financing of mutually agreed projects in areas such as nature conservation and climate or tripartite swaps which involve buybacks of privately held debt financed by donors and/or new lenders, usually intermediated by an international nongovernmental organization (NGO), conditional on nature- or climate-related policy actions and/or investments.

Can DFCS be applied in case of Sri Lanka?

Sri Lanka is ranked among the top 10 countries under Global Climate Risk Index (2018-2020) due to increase in the frequency of extreme weather events such as droughts, floods, landslides and cyclones which would directly affect the financial status of the country as well as the food sovereignty. Therefore, it is essential that Sri Lanka should invest in climate resilient development but given that the island clearly lacks the fiscal space to finance climate investments, as per the working paper, debt swaps and comprehensive debt restructuring can be combined together as financial instruments to overcome both climate vulnerabilities and the fiscal crisis.

In 2021, in a similar situation, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and the Government of Belize (Belize) announced the completion of a USD 364 million debt conversion for marine conservation that reduced Belize’s debt by 12 percent of GDP following which Standard & Poor upgraded Belize’s foreign currency sovereign credit ratings to CCC+/C from SD/SD, or selective default.

Therefore, DFCS and comprehensive debt restructuring could free up some of Sri Lanka’s strained domestic revenue ensuring smooth domestic cash flow for productive investments, and more conservation oriented and climate resilient ventures while enhancing more robust multi-stakeholder partnerships including private sector and other relevant entities.

While DFCS can be of help to Sri Lanka, both fiscally and environmentally, the procedure towards it is very comprehensive and according to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “It requires the concerted efforts of the whole government and very th orough preparations, including pre-feasibility studies, strong fiscal capacity, commitment to transparency and international credibility of the domestic spending and expenditure programme that is attractive to the whole government.” Moreover, only a small portion of the total external debt can be swapped through DFCS and also it is important to make sure that the funds are applied to right projects to ensure sustainability and maximum impact at the ground level. Nevertheless, Debt-for-Climate swaps would be a really good opportunity for Sri Lanka to rebuild the economy while focusing on climate-friendly development.

References:

Chamon, Marcos, Erik Klok, Vimal Thakoor, and Jeromin Zettelmeyer. 2022. “Debt-for-Climate Swaps: Analysis, Design, and Implementation.” IMF Working Paper 2022/162, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

https://www.oecd.org/env/outreach/debt-for-environmentswaps.htm

https://www.nature.org/content/dam/tnc/nature/en/documents/TNC-Belize-Debt-Conversion-Case-Study.pdf

https://www.erd.gov.lk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=102&Itemid=308&lang=en

https://www.landclimate.org/an-imf-bailout-will-not-help-sri-lanka-debt-for-climate-swaps-would/

https://greencentralbanking.com/2023/05/05/sri-lanka-debt-for-nature-swaps/

https://www.thethirdpole.net/en/nature/debt-for-nature-swaps-can-help-south-asia/

DFCS sounds like a very beneficial win-win solution. This method, on the one hand, alleviates the pressure on debtor nations to pay interest, reduces losses for creditor nations, and on the other hand, helps developing countries and small island nations heavily affected by climate change and natural disasters to mitigate and adapt to global climate change. DFCS is quite similar to a range of mechanisms, including Debt-for-Nature Swap, Debt for Adaptation Swap, and Debt for Adaptation Swap, which have been widely applied since its proposal in 1984. As a supplement, here are several classic cases:

(1) In 1987, Conservation International purchased $650,000 of Bolivian debt at a significantly discounted rate of $100,000 using donor funds. In return, Bolivia committed to protecting the Beni Biosphere Reserve and allocated $250,000 (in local currency) for its management.

(2) The largest transaction took place in 1992 with Poland, involving a $580 million debt-for-nature exchange. This transaction introduced a new model, establishing a central trust fund to oversee the selection, implementation, and monitoring of conservation projects. It allowed holders of its $533 million bonds due in 2034 to “trade notes at less than 45% of par,” while also committing $23.4 million to an ocean conservation donation account.

(3) The Seychelles debt swap was the world’s first debt-for-nature exchange project aimed at marine conservation and climate change mitigation. Seychelles, an archipelago nation in the western Indian Ocean, experienced a debt default in 2008. In 2016, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) initiated a “debt-for-nature” agreement that restructured Seychelles’ $21.6 million sovereign debt owed to Paris Club members, primarily the UK, France, Belgium, and Italy, in exchange for its commitment to protect the ocean. The Seychelles government designated 30% of its territorial waters as protected areas, with no unregulated economic activities such as fishing and drilling. As of March 2020, Seychelles had successfully repaid all debt-related payments on time and completed the protection of 32% of its marine territory.

(4) On June 30, 2009, the United States and Indonesia signed a bilateral agreement in exchange for nearly $30 million in debt owed by the Indonesian government to the United States over the next eight years, with Indonesia pledging to use the money for NGO projects benefiting Sumatra’s tropical forests.