In a book by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, I came across an interesting concept that intrigued me. ‘Black Swan’ events coined by the author represents statistically improbable events with profound consequences. But what is the idea behind the term Black Swan?

In Europe, during the Middle Ages, Black Swans were unknown. It wasn’t until Europeans started sailing beyond the continent that these creatures were discovered, no longer mythological but real. Before the finding, this species of bird would have been rare to impossible giving birth to the notion of events so rare, they could go by the name, Black Swan. (Rosen, 2021) The term can now be used to describe something rare and unusual, an outlier from the norm. Black swan events have three important characteristics, these being their extreme rarity, severe impact, and the widespread insistence they were obvious in hindsight.

What makes black swan events so difficult to unravel is precisely because no one sees it coming. It is a blind spot where until the moment a black swan is seen for the first time, we go on with our lives completely oblivious to its existence.

According to Taleb, for extremely rare, surprising events, standard tools of probability and prediction, such as the normal distribution, do not apply since they depend on large populations and past sample sizes that are never available for rare events by definition. Extrapolating, using statistics based on observations of past events is not helpful for predicting black swans, and might even make us more vulnerable to them.

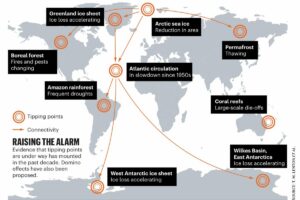

A tipping point in the climate system has been defined as ‘the critical point at which the future state of the system is qualitatively altered by a small perturbation’ (Lenton et al. 2008). These are low probability but high impact shifts, such as the irreversible melting of major ice sheets that could lead to huge increases in global sea levels.

In my view, tipping points are events in between white swans (high degree of certainty such as the planet is getting warmer) and black swans (complete unknowns). These events would be called grey swans, a by-product of the term black swan. Grey swans are not viewed as entirely improbable, meaning the possibility of their occurrence is known beforehand. These are potentially very significant events whose possible occurrence may be predicted beforehand but whose probability is considered small. They can be positive or negative and significantly alter the way the world operates, which is why the IPCC does not discount them and urges us to take them seriously.

Covid-19 is an example of a grey swan. Pandemics are a rare but well-acknowledged risk that the world has experienced repeatedly in the past, from the Justinian Plague to the Black Death and the Spanish Flu (Liberto, 2022). Though the risk of a pandemic in any given year is estimated to be quite low based on past frequency, it is obvious that they have dramatic and transformative effects on society.

While we are aware of the existence of climate tipping points, our approach to them is the same, wherein although we have some amount of theoretical knowledge on the collapse of AMOC, amazon dieback and the irreversible melting of ice-sheets, these low-probability, high-impact scenarios (according to the IPCC) are so complex and unusual that they simply are left out and not factored into future warming scenarios.

During our course, we came across different types of uncertainties. From the known unknowns to the unknown unknowns. Tipping point evidence – whether past tipping points or modelled predictions – involves uncertainty. As for all natural phenomena, the evidence may involve two kinds of uncertainty (van der Bles et al. 2019). We learnt about aleatory uncertainty which arises due to the fundamental randomness of the world. In tipping points, this generally relates to future events, which we can’t know for certain – such as the timing of a future tipping point and the alternate state of an ecosystem that might follow (Newton et al., 2020). A second kind of uncertainty, known as epistemic uncertainty, involves uncertainty about the facts, numbers or science. This generally, but not always, relates to past or present phenomena that we currently don’t know, but could, at least in theory, know or establish – such as the precise cause of a tipping point that has already happened, and how the change might be reversed (Newton et al., 2020).

As we push the climate system to new extremes, we keep moving towards uncharted territory where we cannot anticipate how small changes can potentially destabilise and set off irreversible events much like pulling out a Jenga piece from an already unstable tower.

So, what can be the best approach to dealing with grey swans like tipping points? These kinds of events must be managed by building resilience, or robust capabilities. Perhaps working on factoring in these events into our current IPCC scenarios and pathways so that we are not caught completely off guard like the early explorers when they first came across a black swan is a starting point towards building resilience.

“Our world is dominated by the extreme, the unknown, and the very improbable (improbable according to our current knowledge)—and all the while we spend our time engaged in small talk, focusing on the known, and the repeated.” – Nassim Nicholas Taleb

References:

Taleb, N. N. (2007). The black swan: The impact of the highly improbable (Vol. 2). Random house.

Lenton, T. M., Held, H., Kriegler, E., Hall, J. W., Lucht, W., Rahmstorf, S., & Schellnhuber, H. J. (2008). Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Proceedings of the national Academy of Sciences, 105(6), 1786-1793.

Rosen, L (2021). https://www.21stcentech.com/weather-climate-black-swan-event/

Van der Bles, A. M., Van Der Linden, S., Freeman, A. L., Mitchell, J., Galvao, A. B., Zaval, L., & Spiegelhalter, D. J. (2019). Communicating uncertainty about facts, numbers and science. Royal Society open science, 6(5), 181870.

Newton, Adrian & Watson, Stephen. (2020). Demystifying Tipping Points and other forms of abrupt ecosystem change Valuing Nature Demystifying Series Paper | September 2020 VNP26.

Hey Erika,

I really liked how you frame one of the biggest issues in climate change into the context of The Black Swan. I know this book and heard of some Black Swan events in a different context. Especially, how you put Covid19 as an example here, is very enlightening and makes what we thought, is improbable, more tangible.

Thanks for connecting uncertainty in climate futures with black/ grey swan events. Particularly the quote in the end reinforces me to reflect and question more what happens in the world and what discussions are going in modern times.

Very interesting post Erika! I think the comparison of tipping point events to the concept of black/white/grey swans is a good way to make tipping points more understandable.

An aspect regarding tipping points I learned about in the sea ice lecture and found interesting is that, for example, scientists are not even sure if an tipping point regarding Arctic sea ice melt even exists. Thus, there is not only the uncertainty regarding the impact these alleged tipping points could have but also the uncertainty if they really are tipping points, or if the climate system is more stable than we thought (which is why I really like your Jenga-comparison, because sometimes you think the tower will fall but more and more pieces can be taken out). However, this does not mean we should take out more and more pieces, or regarding our climate system, we should not push it to its limits and hope tipping points will not happen or happen later than anticipated. I agree with your statement that we should deal with tipping points by building resilience. We don’t know if they will happen, but by incorporating them into IPCC scenarios, we could brace ourselves for possible outcomes.

Great post Erika!

The book seems very interesting. I especially liked the quote you put in the end. I will have to give it a read sometime.

You also gave a concise and comprehensible introduction into the concept of white, grey and black swan events.

From my understanding what sets a black swan and grey swan event apart is that we know a grey swan event could appear, and the only thing that prevents it from materializing now is its low probability of occurrence. How could we as a society prepare for such events? Should we even worry about them or focus on the numerous white swans (the societal problems we face) attacking us currently ? If we ignore the warning signs and they do occur the only thing that is certain is that devastation would occur. You have given me a lot to think about!

It would have been interesting to read of more examples of black swans events that humanity has failed to predict and felt the brunt of, but I guess I will have to read the book for that!